Of the 1000’s of races run in the UK and Ireland each year, by far the most common type of contest is the handicap event. With over 50% of races – be they over jumps or on the flat, on turf or the all-weather – taking place under handicap conditions, it makes sense to have a good understanding of how it all works. Hopefully this article will help to shed a little light on an area of racing which really isn’t as complicated as it may initially appear.

Of the 1000’s of races run in the UK and Ireland each year, by far the most common type of contest is the handicap event. With over 50% of races – be they over jumps or on the flat, on turf or the all-weather – taking place under handicap conditions, it makes sense to have a good understanding of how it all works. Hopefully this article will help to shed a little light on an area of racing which really isn’t as complicated as it may initially appear.

As mentioned, handicap races take place under both the flat and National Hunt codes, and whilst they often don’t boast quite the prestige and value of their Group and Graded race cousins, as we can see from the tables below, the handicap category still houses any number of cracking contests, including of course, the most famous race of them all: The Grand National.

Major Handicap Races

The Aim of Handicap Racing

First things first. Why bother having handicap races at all? The aim of handicap racing is to create as level a playing field as possible, and – at least in theory – give each of the runners in a handicap race an equal chance of winning. This is achieved by assigning weights to be carried by each of the runners according to their ability. The better the horse, the more weight they will carry.

How Is the Handicap Determined?

So, how are the exact weights carried determined? This is where the official handicapper comes in. It is his job to assign a numerical value to the ability of each and every horse in training by viewing their previous race course performances. Horses must initially have either won a race, or run three times, in order to be assigned an official rating and therefore become eligible to run in a handicap event. Ratings are continually updated after each and every race, with the latest list of ratings being released every Tuesday.

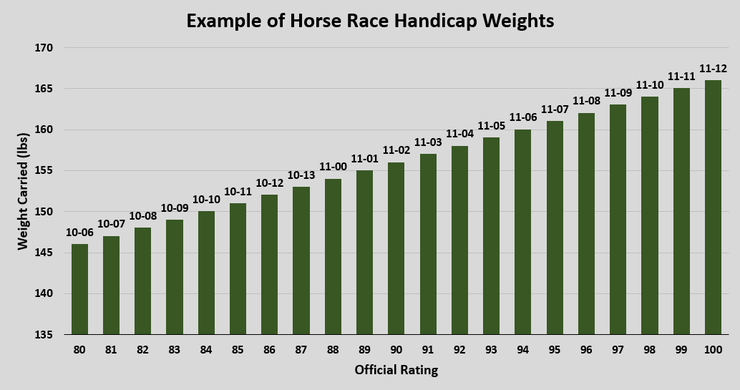

We now have the ratings, but how does this correlate to the weight to be carried by each runner? Thankfully, this part is very straightforward. Consider a handicap race containing one runner with an official rating of 90 and another rated 85. The 90 rated runner would be required to carry 5lbs more than the 85 rated horse. One ratings point equates to one pound in weight.

Handicap Races & Grades

With so many horses in training, the range in ability between runners can be vast. From your lowly handicapper with a rating of say 55, right up to the 140-rated Frankel. The difference in ratings here would correspond to a weight difference of a whopping – and unfeasible – 6st1lb should these two runners meet in a handicap.

This is admittedly an extreme example, but serves to illustrate a point. In order to enable runners of broadly similar abilities to compete against one another, we need to break down the handicapping sphere into smaller groups or classes. In descending order in terms of ability of runner, these classes range from 1-7 on the flat and 1-6 for National Hunt racing. See tables below for a definition of which horse are eligible to race in which Class.

Flat Racing Handicap Classes

| Class | Notes |

|---|---|

| Class 1 | For runners rated 96-110+. These tend to be Listed events. |

| Class 2 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 86-100, 91-105 or 96-110. |

| Class 3 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 76-90 or 81-95. |

| Class 4 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 66-80 or 71-85. |

| Class 5 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 56-70 or 61-75. |

| Class 6 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 46-60 or 51-65. |

| Class 7 | For runners rated 0-45. These tend to be Classified Stakes events. |

National Hunt Racing Handicap Classes

| Class | Notes |

|---|---|

| Class 1 | Non handicap races, i.e. Grade 1, Grade 2, Grade 3 and Listed events. |

| Class 2 | Open handicaps for runners rated 0 – 140+ |

| Class 3 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 0-120 and 0-135. |

| Class 4 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 0-100 and 0-115. |

| Class 5 | Usually restricted to runners in the following bands: 0-85 and 0-95. |

| Class 6 | Generally non-handicap National Hunt Flat races or Hunter’s Steeplechases. |

Note that whilst the bands for National Hunt racing are very broad, this very rarely results in runners of vastly different ability competing against one another. The maximum field size stipulation sees to this. Every race will have a maximum field size on safety grounds, and preference will be given to the higher rated runners. So for a race which has 50 entries but a maximum field size of 20, it will be the 20 highest rated runners who are allowed to line up on the day.

Out of the Handicap

When looking at handicap races, chances are you will from time to time come across a runner said to be “racing off its long handicap mark”, being “wrong at the weights” or “racing from out of the handicap”. These three terms essentially all boil down to the same thing. Namely that said runner will be carrying more weight than they should be according to their official rating. But how and why does this happen?

This occurs due to each race having a stipulation about the minimum and maximum weight to be carried. For example, we may see a Class 4 0-140 Handicap Hurdle with a maximum weight of 11st 10lb and a minimum of 10st. Now consider that the top-rated runner in the field is rated 140 and the lowest rated horse in the line-up is on a mark of 112. The 140-rated runner will carry the maximum weight of 11st 10lb, so on ratings the 112-rated runner should carry 28lbs less than this, or 9st 10lbs. However, as the minimum weight to be carried is defined as 10st, this horse must still carry 10st putting it at a 4lb disadvantage.

Ahead of the Handicapper

Another phrase you may hear when looking at handicap races is that of a certain horse being “ahead of the handicapper” or “well in on the handicap”. This is sometimes used merely as an opinion; that is, that a certain horse appears to be progressing at a rate not fully accounted for by his increased handicap mark, but there are instances when certain runners are officially “well in on the handicap”.

The weights for certain handicaps are announced a week or more in advance of the race – often considerably earlier for major events, such as the Grand National – and as such it is possible for a runner to win a different race between the time that these weights are announced and the race taking place. There are measures in place to counteract this in the form of weight penalties for winning a race – usually between 3lb and 7lbs – but they aren’t always enough to compensate for the rise in handicap mark.

Let’s consider the following example: a horse by the name of Paul The Plotter is assigned a mark of 137 on the 16th March for the Topham Handicap Chase which takes place on the 5th April. Paul The Plotter subsequently hacks up in his prep race for the big one and is reassessed the following Tuesday and handed a new mark of 148.

The terms of the Topham state that Paul The Plotter must now carry a 4lb winner’s penalty in the race, but his initial mark will remain 137 as initially assigned. As such we can see that this horse would be 7lbs well in on the official handicap on the day of the race. He will be running of 137 plus his 4lb penalty, so effectively 141, but should actually be competing off 148. Such runners are always worth a second look in the betting.

In flat racing – where horses can run more frequently – this situation can occur more often. It’s quite possible for a runner to be handed a mark of 65 on the Tuesday when the ratings are released, then win a race by 10 lengths on the Wednesday, before running again on the Saturday under just a 3lb penalty. Likely to be reassessed somewhere in the mid 70’s when the new ratings are released on the following Tuesday, we can see that this runner was well in for that second run.