The West Coast racetrack of Galway is one of the most popular in the whole of Irish racing and it is a venue that is embedded in the culture of this most racing-loving of nations. Situated in the town of Ballybrit, around six miles outside the city of Galway, the track first opened for business in 1869 and wasn’t long in gaining in popularity, with no fewer than 40,000 racegoers turning up for that very first meeting.

A dual-purpose venue, the track benefits from two grandstands and excellent facilities throughout, which, combined with strong transport links to the vibrant city of Galway itself, makes this a must-visit course for many racing fans.

Any racegoers who are hoping to take a trip to Galway – known as Ballybrit Race Track to locals – aren’t particularly spoilt for choice in terms of fixtures, with the track staging only 12 race days per year, two in September, three in October and of course the seven-day extravaganza that is the Galway Festival in late July/early August each year. Attracting in excess of 140,000 racegoers, it is that summertime mixed flat and jumps meeting which has elevated Galway to such a prominent position on the racing landscape.

Racecourse Facts

Course Summary

Looking at the track itself, Galway’s dual-purpose course features an oval layout that definitely veers towards the circular; turning almost continually throughout, other than in a final straight run to the line – it isn’t quite Chester, but it isn’t too far off it!

Measuring a shade under 1m3f in circumference, and undulating in nature, Galway is an easy course for much of its duration. That is until the runners reach that final run-in of just over a furlong. Widely viewed as being one of the stiffest finales in all of Irish racing, this closing section rises steeply all the way to the line, and will lay bare any stamina limitations, both on the flat and over jumps. Tough at the best of times, the finish can become a real slog on soft or heavy ground – far from an unusual occurrence at a track that is no stranger to the rain.

Given its fairly unique demands, it is no surprise that Galway is known as something of a specialist’s track. Previous course winners are always worth a second look, with a number of runners having racked up a sequence of wins here in the past – including One Cool Poet, who spectacularly won three races in the space of just five days at the 2019 Galway Festival. Some feat!

Notable Trends

Not only is this track tricky for the horses, but it also particularly challenging for those in the saddle; with a fine judgement of pace and knowing where and when to best get a breather into their mount often proving to be the difference between winning and losing. With that in mind, it is always worth taking note of riders who have previously shown they have what it takes at this unique track.

Flat rider Donnacha O’Brien and jumps jockey Barry Geraghty were the clear standouts in the saddle here during their careers. Unfortunately for trends fans though, both have now retired, leaving current flat jockey W J Lee (19% strike rate, level stakes profit above £7) with the best record in recent seasons. Geraghty aside, no other jumps jockey has managed to show a level stakes profit over this period.

Willie Mullins is a man more associated with success over jumps, but the Clossutton maestro has been well worth following in flat contests here, boasting an impressive 34% strike rate and a whopping profit of almost £56 to £1 level stakes over recent times.

The most surprising finding in the latest results is just how well the favourites have performed at what is one of the most competitive tracks in the country. Backing the market leader in all non-handicap flat contests would have returned a 55% strike rate and level stakes profit of over £21, whilst the figures in 3yo handicaps (39% strike rate, over £13 level stakes profit are also encouraging. The picture over the jumps isn’t quite so rosy, but handicap chases have fared well (36% strike rate, over £15 level stakes profit).

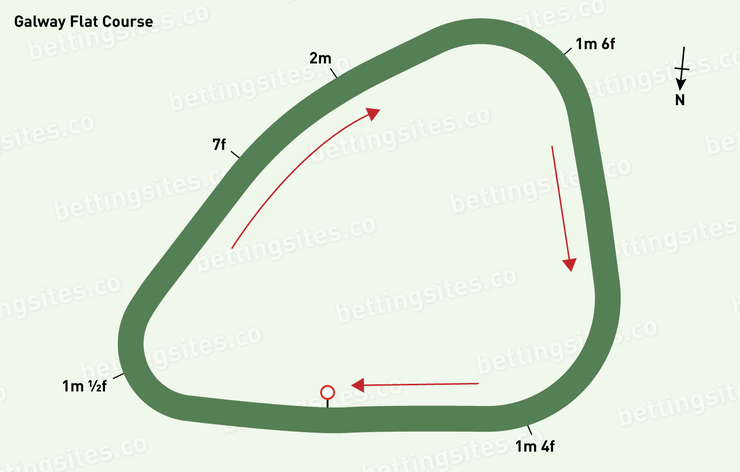

Galway Flat Course

One of the first things to jump out about flat racing at Galway is the lack of sprint races at the venue, with the track staging events over distances of 7f, 1m½f, 1m4f, 1m6f and 2m. As mentioned, each circuit measures close to 1m3f and features both ascents and descents; the most significant of which come in the sustained downhill section which leads into the home straight, and the demanding climb to the line of the home straight itself.

When looking at the type of runner to be favoured around here, all of the usual tight course criteria apply. Nippy sorts who like to race prominently and are able to maintain their momentum around the tricky turns are at an advantage over the more galloping types who may struggle to build up a head of steam. Prominent racers, or out and out frontrunners are well worth a look on the level, particularly over the 7f and 1m½f trips. That said, any prominent racer is still going to need to fully stay the distance if they are to prevail. It is hard to overstate just how tough that final run-in is, particularly as races tend to be big field affairs that are often run at a frenetic pace.

Finally, be very wary of hold-up performers at Galway. Not only is the layout of the track not particularly conducive for those who like to come from behind, but that gruelling finish often results in prominent racers with stamina concerns dropping back through the field, creating significant traffic problems for those looking to come with a late flourish.

The Draw

The most logical place to expect a draw bias at Galway would be in the 7f events, due to the proximity of the starting stalls to the first bend. And when looking through the results at the track, it turns out that the data does back up this theory. An analysis of 30 contests over the distance shows a combined win and place percentage of 34.51% for low drawn runners, 26.41% for middle, and 21.71% for high. Overall, this bias is stronger on good or quicker going, and decreases steadily as race distance increases, becoming a non-factor over the staying trips.

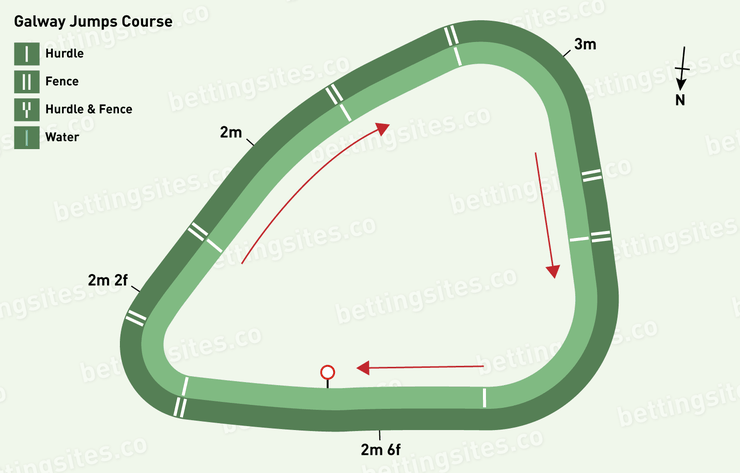

Galway Jumps Courses

The chase course uses the outer portion of the track and features seven fences per circuit – one just after the winning post, four in the back straight and two in the shorter straight section before the turn for home. With no water jumps or open ditches, and not being particularly stiff, the fences aren’t especially difficult in and of themselves. However, the two before the home turn can prove very tricky for suspect jumpers, coming as they do on a downhill section of the track, and lying closer to one another than any other pair of fences in the whole of world racing. Meeting the first of the obstacles on the right stride is key to navigating this section, and if there is to be a jumping error in a race it is most likely to come here. Having negotiated this final obstacle, runners are then faced with a run in of over two furlongs, most of which comes in that stiff uphill home straight.

Utilising the inner portion of the track, the hurdles course is that bit tighter than the chase course and features a total of six flights per circuit – one just after the winning post, three in the back straight, one before the turn for home, and one in the home straight itself, resulting in a relatively short run-in of only around a furlong.

Be it over hurdles or fences, the National Hunt track favours those runners who enjoy racing around tight turns, with proven stamina at the distance also a key factor for success. Prominent racers also tend to do be favoured, although this bias is notably stronger over the minimum trips, becoming significantly less of a factor as the race distance increases.