Located only around 1km outside of the town of the same name in the northwest of Ireland, this small but charming racecourse lies just a stone’s throw away from the urban hub of this popular tourist destination. Not that you would know it when viewing the action at the track though, with the beautiful backdrop of the Dartry Mountains making this one of the most scenic racing venues in the whole of the Emerald Isle.

Racing in this corner of Ireland dates back to 1781, with the nearby Rosses Point having staged the first formally recognised events. Dotted around a number of locations in the intervening years, it wasn’t until 1955 that the first meeting was staged at its current home of “Pump Field”. Also known as Cleveragh to Irish racegoers, Sligo Racecourse continues to go from strength to strength in the modern era. Benefitting from significant investment in 2013 – funding a new grandstand amongst other improvements – the track provides one of the best country race day experiences that Ireland has to offer.

Racecourse Facts

Course Summary

Sligo plays host to both flat and National Hunt action, staging a total of eight fixtures between late April and early October each year. Firmly focussed on attracting the tourists and catering to the recreational racegoer, the majority of these meetings are punter friendly evening fixtures. There are no real standout events at this track, with the emphasis placed upon competitive rather than high-class action. However, this has proven to be no hindrance to drawing in the crowds, with the two-day August meeting, including a ubiquitous “Ladies Day”, proving particularly popular.

The fact that Sligo’s fixtures take place exclusively outside of the winter months, does mean that the track gives itself the best chance of avoiding the worst of the weather. It’s impossible to escape the rain in Ireland entirely though, and be aware that when the going is described as heavy at Sligo, it really does mean heavy! Lying at the base of a natural bowl, water tends to flow and collect on the course, creating truly gruelling conditions when the heavens open.

Notable Trends

One of the more challenging courses to ride in Irish racing, the mounts of any rider with a proven record at the venue are always worthy of close inspection. And looking at the results of the past few seasons there are a number of jockeys who seem particularly adept at negotiating Sligo’s turns and undulations. With a strike rate of 31% and net win of over £27 to £1 level stakes, Gary Carroll leads the way on the flat, with Shane Cross (40% strike rate, over £12 level stakes net win) the other name to note. Over jumps, big-name riders, Paul Townend (32% strike rate and just under £14 level stake net win) and Davy Russell (23% strike rate, around £19 level stakes net win) have fared well, as has the lesser-known Kevin Brouder (25% strike rate, around £14 level stakes net win).

Turning to the trainers, and there are again certain handlers who seem particularly attuned to identifying the right type needed to succeed. Jessica Harrington (36% strike rate, over £13 level stakes net win), Michael Mulvany (29% strike rate, over £15 level stakes net win) and Joseph Murphy (40% strike rate, over £22 level stakes net win) have rewarded support on the flat, with Mark Michael McNiff (17% strike rate, around £29 level stakes net win) and Mouse Morris (44% strike rate, over £8 level stakes net win) performing well over jumps.

This is a relatively poor track for supporters of the market leader, the only route to a net win has come in the non-handicap events for runners aged four and older on the flat, with such contests returning an impressive 58% strike rate and over £6 level stakes net win.

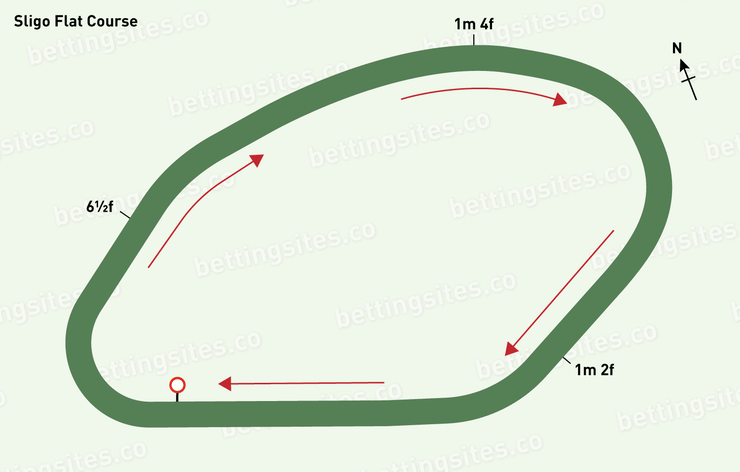

Sligo Flat Course

The track itself is a right-handed oval of only a shade over a mile in circumference. A notably tricky course, runners are on the turn to some degree for a significant portion of each circuit which, in combination with the undulating nature of the terrain, tends to favour nimble, well-balanced types.

Taking in a circuit beginning at the winning post, the field initially turns sharply right-handed around a long downhill section of the track as they head away from the stands and to the bottom of the hill. Continuing to turn right-handed, it is around four furlongs from home that the track then begins to climb, and it continues to do so all the way around the final bend and throughout the one and a half furlong run-in, resulting in a finish which is regarded by many jockeys as being amongst the stiffest in Irish racing.

Overall, the sharp, undulating nature of the course naturally suits those who like to race prominently. However, it is still vital that riders judge the pace correctly, as those setting off too quickly are likely to find the gasometer flashing red on that climb to the line. It does seem that the majority of jockeys bear this in mind though, with the results over the years suggesting that front runners/prominent racers are strongly favoured over all distances.

Low drawn runners appear to be at a slight advantage at distances between six furlongs and 1m2f. This edge is however only relatively slight – surprising given the turning nature of the track – and becomes increasingly insignificant over longer distances.

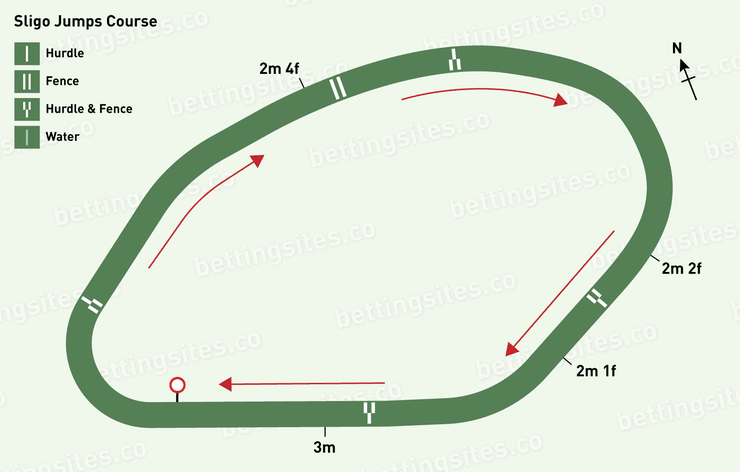

Sligo Jumps Course

All National Hunt events are held on the same track used in flat contests, with the chases taking place on the outer portion of the track, and the hurdles utilising the inner. Those tackling the chase course are faced with five moderately stiff fences per circuit – four plain and one open ditch – with the final obstacle coming in the home straight around a furlong from home.

The hurdles course features just four flights per circuit, with the track using the artificial EASYFIX style of obstacle. In common with the chase track, the last of the jumping challenges lies in the home straight, creating a run-in of close to a furlong.

When looking at the type of runner favoured, in common with the flat events, it can pay to side with the speedier sorts who like to race up with the pace, as even on heavy ground it can prove very difficult to come from behind around here. Runners with a good position entering the home straight tend to stay there come the finish line.